15% off eLearning, up to 20% off live virtual classroom - use code: EARLY2504SA

27 November 2018 | Updated on 6 January 2025

Building a credible, capable and competent workforce – an enterprise-level approach. Part 1

One of the more enlightening conversations I can remember having with a board of directors was when I was suggesting that perhaps, given that the company was in a remarkably bad position at the time,...

One of the more enlightening conversations I can remember having with a board of directors was when I was suggesting that perhaps, given that the company was in a remarkably bad position at the time, we should look at the competence of the people managing our projects. We had just written off around £700 million in underperforming projects, so there was certainly some evidence that the competency of the workforce was questionable – indeed, KPMG had been employed to identify the reasons behind the failure, one of which was reported as being that the ‘wrong PM’ had been appointed. But what do we mean by the ‘wrong’ PM? What would ‘right’ look like?

There were many varied reasons behind the poor performance of the organisation but, ultimately, asking an expert to leave behind their specialism and manage a project without significant input on how to manage a project, its people and its finances, is courting disaster. It seems blindingly obvious that a project manager needs to be competent in managing a project, but that’s the problem with the blindingly obvious – it’s blinding! So, let’s take the proverbial ‘blinkers’ off, and explore a method for determining the true competence of your project management community.

There’s a lot to say on this topic, so I’m splitting this post in two: part 1 offers some guidance on defining a job family and selecting the right competencies; part 2 looks at creating a rating system that works for your organisation, along with a suggested starting point.

Getting started

For the first step, I recommend a professional review of the job family within which the PM community reside. At the basic level, a job family is simply a method of categorising employees into groups that share a common skill or type of work. Grouping people by job family, as opposed to division grade or location, is a powerful way of creating communities of practice which can be utilised for many different initiatives. Then, ask yourself: does the job family cover project, programme and portfolio (P3) levels? How many of the personnel in the job family have job titles that are truly part of the PM role? How will those roles change/evolve in the future, particularly if the reason for your review is as part of a transformational change for your organisation, and so on.

So, review the form and function of the P3M job family, which should include no more than ten different roles, and start with the obvious: the project manager. Ask yourself questions such as:

- What would you call someone who is more senior than a PM?’

- What would you call someone who is not quite a PM?

- What would you call someone who has just joined the organisation and will be developed over time to become a PM?

Then, from the bottom up, you’ll probably have something that looks like this:

- Trainee PM (typically grad-entry level)

- Assistant PM

- Project manager

- Senior PM

Continuing this logic, there is of course a point where a project, due to size, complexity, strategic outcome focus, etc., becomes a programme. Yes, you guessed it, we need a programme manager! The programmes and projects will then, when coupled with BAU activities, become the portfolio, for which we will need… a portfolio manager!

- Programme manager

- Portfolio manager

This would represent what I would call the ‘core’ roles within a P3M job family, but depending on the industry, size of the organisation, variety and complexity of the P3 carried out, etc., others may be required; for example, project director and portfolio director. By the end, you may have something like this:

- Trainee PM – support focus

- Assistant PM – support focus

- Project manager – tactical focus

- Senior PM – tactical focus

- Project director – strategic or tactical focus

- Programme manager – strategic focus

- Portfolio manager – strategic focus

- Portfolio director – strategic focus

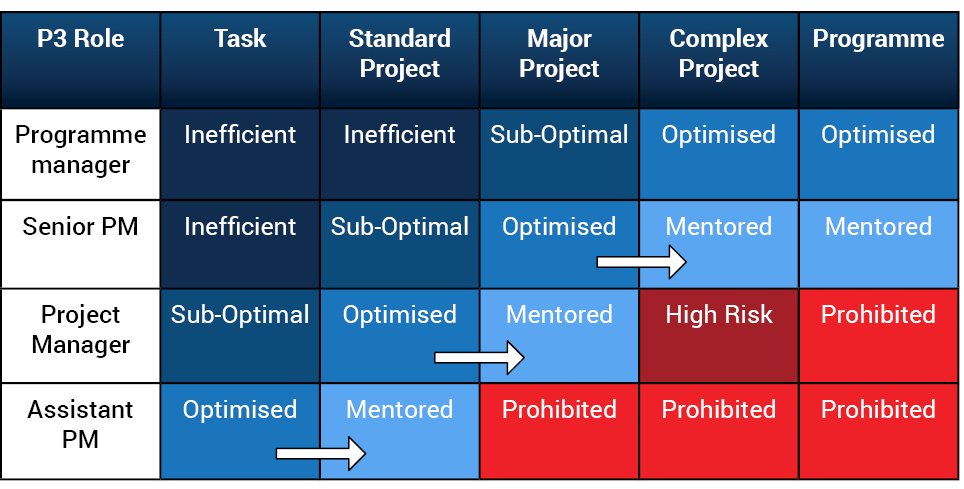

Having created the roles within the job family, and agreed them with all key stakeholders, we now need to establish what ‘competent’ looks like for each of these roles. Essentially, this means selecting a list of competencies that apply to each role and determining at which level an individual would be deemed competent, taking into account what they are expected to do in that role. ‘Competent’ as a statement, and the competencies that constitute that statement, must therefore be linked to the complexity of the project or programme being managed. The diagram below is an example using standard terminology for project complexity, and some of the P3 roles derived earlier.

Selecting the competencies

To start, we need to agree on a standard set of competencies – my own preference is to use an internationally-approved standard such as those from the Chartered Association for Project Management, the APM or the Project Management Institute (PMI). This is not as difficult as it seems – simply write each competency in the manner of the standard ones, with a descriptor and a suitable number of indicators. Of course, which standard you choose will depend on the complexity and needs of your organisation and your projects. Once this process is complete, you will be in the proud possession of a (draft) competency library for your P3 community – well done, so far so good!

So, continue by setting up competency workshops with representative individuals, selected by the senior management for each division affected, who represent someone operating well at the level expected. Six to ten personnel will work well, but ensure you have adequate coverage of all areas of the business from each role within your P3M job family.

Using your chosen standard, select ten or so basic competencies, such as risk management, scheduling, communication, planning, change management etc. My personal preference here is to use the APMCF version 1, as it is broader – it contains 47 competencies in total – but feel free to use whichever standard suits you best. These chosen competencies will enable the team to understand the direction of travel and, in doing so, become familiar with the structure of each competence, along with the cadence of its associated ‘indicators’ and the intricacies of the scoring mechanism.

After having agreed the first set of standard competencies, I suggest a very quick ‘yes or no’ decision – i.e. the competency either does or does not apply to this role in this organisation.

We’re going to cut it off there for the time being, but in part 2 we’ll be looking into how to establish a competency rating system, and how to start your own study.

In the meantime, our consultants can help you with assessing competency both at an organisational and on an individual level with our proprietary 3CAT tool, which is based on the APM’s competency framework. Our 3CAT tool enables you to measure your team’s project management competency through simple self-assessments, and identify key areas for development.

For more information on how we can help you with competency assessment, visit our website or get in touch with us on 01270 611 600.